Latest Research

Current Research related to Structural Integration and Rolfing®

More and more research is being published about Rolfing SI. Below are summaries of the most recent publications on Rolfing SI research – including studies on Low Back Pain, Fibromyalagia, and Cerebral Palsy.

The Latest in Structural Integration Research

We have also been keeping and updating a reference list available for anybody to download below. This is research published in peer-reviewed journals or conferences and briefly introduces what has been done in the field. Part of the list is a reference to the Fascia Research Congress as well.

List of references for current research

The DIRI Research Committee is also gathering interesting use case studies and references that can be useful for practitioners and students in Rolfing SI. We will publish these soon here as well.

Dr. Pedro Prado shares lots of interesting literature and use cases also in his web library. He made his Ida P. Rolf Library of Structural Integration available at novo.pedroprado.com.br.

A more comprehensive and updated list of research literature on Structural Integration (including Rolfing) can be found on the Ida Pauline Rolf Research Foundation (IPRRF) web page: rolfresearchfoundation.org/research/structural-integration-library/.

Structural Integration and Back Pain

Structural Integration as an Adjunct to Outpatient Rehabilitation for Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain: A Randomized Pilot Clinical Trial.

Eric E. Jacobson, Alec L. Meleger, Paolo Bonato, Peter M. Wayne, Helene M. Langevin Ted J. Kaptchuk, and Roger B. Davis

A randomized a clinical trial conducted at Harvard Medical School and Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital compared the Ten Series of Rolf® Structural Integration (SI) as an addition to the current standard of outpatient rehabilitation (OR) to OR alone for chronic low back pain (n=46). Median reductions in pain intensity (visual analog scale, 0-100 mm), were −26 mm in SI+OR compared to 0 mm in OR alone but were not significantly different between groups (p=0.075, Wilcoxon rank sum). However, median reductions in back pain-related disability (Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, 0-24 points) of −2 points in SI+OR compared to 0 in OR alone was significantly different both statistically (p=0.007) and clinically. Other significant differences were found in the Bodily Pain sub-scale of the Short Form 36 Health Survey (p=0.009) and patient-rated Global Satisfaction with Care (p=0.0003), both being more favorable in SI+OR compared to OR alone. Exploratory analysis with a linear mixed model estimated the average rate of reduction in the visual analog scale of pain across the 20-week duration of the study as significantly greater in SI+OR than in OR alone (p=0.0039). Adverse events (AE) related to participation in the study were mild to moderate (none were serious) and self-limiting (none required medical treatment). Neither the proportions of subjects with AE nor the seriousness of AE were significantly greater in SI+OR compared to OR alone.

These outcomes suggest that the addition of Rolf® Structural Integration to outpatient rehabilitation is likely to result in a significantly greater improvement in disability at least in the short term, with no significant increase in the incidence or seriousness of AE. Feasibility data on subject recruitment, retention, and compliance with treatment assignment suggested that a larger, more definitive trial would be feasible.

The principal investigator was Eric Jacobson, and co-investigators were Alec Meleger, Paolo Bonato, Ted Kaptchuk, and Roger Davis. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov prior to beginning recruitment (NCT01322399). Funding was provided by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health at the National Institutes of Health (K01AT004916), the Ida P. Rolf Research Foundation, Harvard Medical School, the Rolf Institute® of Structural Integration, Dean Rollins, and Hal and Sonja Milton. The primary publication is available online at www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2015/813418

Correspondence should be addressed to Eric E. Jacobson; ericjacobson@hms.harvard.edu

Received 7 November 2014; Revised 8 January 2015; Accepted 8 January 2015

Academic Editor: Jenny M. Wilkinson Copyright © 2015 Eric E. Jacobson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

1. Jacobson E, Meleger A, Bonato P, Wayne P, Langevin H, Kaptchuk T, Davis R. . Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015:813418, 2015.

© Copyright Eric Jacobson 2016

Rolfing® SI and Cerebral Palsy

Myofascial structural integration therapy on gross motor function and gait of young children with spastic cerebral palsy

Rolfer® Karen Price collaborated with Heidi Feldman, Alexis Hansen, and others on three studies of Structural Integration for children with spastic cerebral palsy (CP) at the Department of Pediatrics, Stanford School of Medicine from 2009-2015. Price provided all SI treatments in each study.

The following summary was prepared by Eric Jacobson in consultation with Karen Price and Alexis Hansen.

Study I was conducted in 2009-10 and was a randomized trial of SI versus play therapy. This was a cross-over design in which 8 CP children aged 2 to 7 years with mild to moderate spasticity, were initially randomized to 10 weekly sessions of SI or to the same number and frequency of play therapy sessions, and were then switched to the other treatment for another 10 weeks. Data was collected at baseline and after each treatment phase. The primary outcome was the Gross Motor Function Measure-66 (GMFM) which assesses 5 dimensions of motor performance and was scored by a clinician blind to treatment assignment. Secondary outcomes were passive ankle range of motion (ROM), an Observational Gait Scale that was scored from videos, parent reports on the Child Behavior Checklist and the International Classification of Function, and parent-rated satisfaction with care at an exit interview.

Outcomes: 6/8 children had improvement in GMFM during SI and one deteriorated. There was no consistent improvement in ankle ROM or International Classification of Functioning. At the exit interview parents reported improvements in health and well-being: appetite (n=5), bowel function (n=1), speech (n=2), drooling (n=3), and mood and maturity (n=4). The average parent-rated satisfaction was 9.6 out of 10.

Funding for the participation of investigator Alexis Hansen was provided by the Stanford Medical Scholars Program.[1,2]

Study II conducted in 2011-13 consisted of case studies of two male children with spastic CP, aged 6 and 7, who received 10 weekly sessions of SI from Karen Price. Gait data were collected electronically using a GAITRite® walkway prior to the first and immediately, at 3 and 6 months following the tenth treatments.

Outcome: At baseline gait parameters for both children varied significantly from normative values. Visual inspection of the plots of cadence and double support time suggested movement toward normative values immediately following the 10th SI treatment. Those improvements were maintained at 3 months later but returned to baseline values at 6 months after treatment.

Funding was provided by a research grant from the Gerber Foundation (11PH-010-1210-2936). The participation of co-investigator Christina Buysse was supported by a grant from the Maternal Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration (T-77MC090796).[3]

Study III was conducted during 2011-15 with children with moderate to severe spastic CP, age< 4 years, in two phases. The total enrollment over both phases was 29 subjects. In both phases, each child continued their established therapeutic regimen which included physical therapy at a minimum and also possibly occupational therapy, medication, other complementary treatments, and recreational activities. The primary outcome was the GMFM. The secondary outcome was a parent satisfaction survey which included questions about the child's emotional affect, functional body control, balance/flexibility, strength, height, weight, functional achievement, open-response questions, and ratings of parental satisfaction and their child's satisfaction.

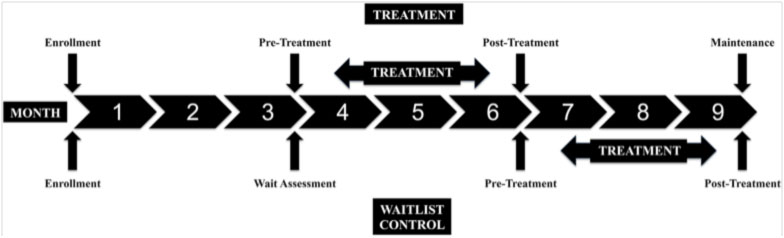

Data were collected at baseline, 3, 6, and 9 months. (Figure 1) This included a three-month run-in period during which no subjects received treatment in order to assess the rate of change in motor performance that occurred due to development and usual care alone. Between months 3 and 6 the SI group received treatment and Wait List control continued usual care. Between months 6 and 9 those subjects who had been on the Waitlist received SI treatment. The SI group had follow-up data collected at 6 and 9 months.

Figure 1: Timeline of treatment phases and data collection points. (Treatment=10 sessions of SI; Wait List=continue ongoing usual care)

Used by permission of the authors.[4] Copyright under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode

Phase 1 randomized 26 children to ten weekly sessions of SI (n=13) or Waitlist (n=13). One dropout from each arm and the reassignment of 3 from the Waitlist to SI treatment resulted in 6-month data available for 15 in SI and 9 on Waitlist. GMFM ratings were performed by a clinician who was blind to treatment assignment.

Analysis of the primary outcome (GMFM) was a repeated measures ANOVA that included time (assessments 2 and 3) and group (SI versus Wait List). There was a significant improvement in all children over time (p=0.009), but no significant difference between groups in the rate of change (p=0.350).

Phase 2 was an open-label extension in which the clinician assessing the primary outcome (GMFM) was not systematically blinded, and which included 5 additional children who met the Phase 1 entry criteria and who were all assigned to SI treatment. This increased the available sample size for SI (n=20), compared to Wait List (n= 9).

Analysis of the primary outcome (GMFM) was the same repeated measures ANOVA model as in Phase 1 analysis, including time (assessments 2 and 3) and group (SI versus Wait List). There was a significant improvement in all children over time (p=0.004), but no significant difference between groups in the rate of change (p=0.256).

A pooled sample analysis included all subjects who had completed data collection at all four assessments - baseline, 3, 6 and 9 months (n=27). Analysis of the primary outcome (GMFM) was a repeated measure ANOVA including time (all four assessment points) and group (SI versus waitlist). There was a significant improvement in all children over time (p=0.000), but no significant difference in change between groups (p=0.420).

Electronic gait data (GAITRite® walkway) was collected from 8 of the 29 children who were ambulatory at enrollment. A comparison of six gait parameters pre versus post-SI treatment found that foot length on the more affected side increased (p=0.04, paired sample t-test), and had not increased during the pre-treatment interval (p=0.76). The five other gait parameters had no significant change.

Parent satisfaction at exit interviews (n=25) averaged 8.4 out of 10, and their rating of child's satisfaction averaged 8.6. Many parents reported qualitative improvements in their child's motor skills.

Conclusion: SI treatment as a complement to usual care for children with spastic CP did not increase their rate of change in GMFM beyond that occurring due to development and usual care alone. In ambulatory subjects, SI treatment was associated with increased foot length on the affected side, possibly due to improvements in heel strike and gait quality. Parents generally found SI to be beneficial in ways not captured by the main outcome measures. Further assessment of manipulative therapies in this population are warranted and might include other measures of movement, spasticity, quality of life, and functional changes in domains, such as mobility, self-care, communication, and social function

Funding: The study as a whole was supported by funding from the Gerber Foundation (11Ph-010-1210-2986). The participation of co-investigator Tina Buysee was supported by a Maternal Child Health Bureau Training Grant, Health Resources and Services Administration (77MCO9796-01-00)[4]

Additional reports: Two conference posters presented GMFM data from the early stages of study III, and another presented results of gait studies with a larger sample than what was reported in Loi et al. 2015.

A poster presented at the 2013 meeting of the Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics (SDBP) reported on outcomes from the first 16 enrolled children. In Phase 1 they were randomly assigned to either 10 weekly SI treatments (n=8) or to Waitlist (n=8). After 10 weeks, the children who had been in Wait List were then provided with SI treatment. GMFM ratings were provided by a clinician blind to treatment assignment.

Analysis of data from both groups pooled together (n=16) found a significant reduction in GMFM scores pre- to post-SI treatment (p=0.046, paired t-test), and no significant difference in scores pre to post the 3-month period immediately prior to SI treatment (p=0.169). A secondary analysis used a repeated measure ANOVA that included time (assessments 2 and 3) and group (SI versus waitlist) and found a trend to significant change pre versus post-SI treatment for the sample as a whole (p=0.14), but no significant difference in the rate of change between groups.[5] The same information was also reported in a poster at a University of California San Francisco student symposium, 2014.[6]

A poster presented at the 2015 SDBP meeting reported a gait study with a sample of 9 CP children < 4 years old, which included 8 of the 29 children in study III who were ambulatory at enrollment, plus one additional child. Electronic data on gait were collected (GAITRite® mat). The analysis compared pre- to post-SI treatment values for six gait parameters. There were significant differences in foot length (p=0.02, paired t-test), and differences in the heel-to-heel base of support trended to significance (p=0.06). Pre to post-treatment comparisons of five other gait parameters were non-significant.[7]

References

1. Hansen A. B., K. S. Price, H. M. Feldman (2012). Myofascial structural integration: a promising complementary therapy for young children with spastic cerebral palsy. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 17(2), 131-35.

2. Hansen A., Price KS, Feldman HM (2010). Myofascial treatment for children with cerebral palsy: a pilot study of a novel therapy. Pediatric Academic Society Annual Meeting. Vancouver, BC, Canada: May 2010

3. Hansen A., Price KS, Loi EC, Buysse CA, Jaramillo TM, Pico EL, Feldman HM. (2014). Gait changes following myofascial structural integration (Rolfing) observed in 2 children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Evidence Based Complmentary & Alternative Medicine, 19(4), 297-300.

4. Loi ED B. C., Price KS, Jaramillo TM, Pico EL, Hansen AB, Feldman HM. (2015). Myofascial structural integration therapy on gross motor function and gait of young children with spastic cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 3(74), 1-10.

5. Loi E., Buysse CA, Hansen AB, Price KS, Jaramillo TM, Feldman HM (2013). Gross motor function improves in young children with spastic cerebral palsy after myofascial structural integration therapy. Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics Annual Meeting September, 2013

6. Findley N., Jaramillo TM, Loi EC, Buysse CA, Hansen AB, Price KS, Feldman HM (2015). Gross motor function improves in young children with spastic cerebral palsy after myofascial structural integration therapy. University of California,San Francisco, student symposium.

7. Buysse C., Loi ED, Price KS, Jaramillo TM, Hansen AB, Pico EL, Feldman HM (2015). Gait improvement in children with cerebral palsy after myofascial structural integration therapy. Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics Annual Meeting 2015.

© Copyright Eric Jacobson 2016

Rolfing® SI and Fibromyalgia

Clinical trials of Rolfing for fibromyalgia conducted by Paula Stal and summarized by Eric Jacobson.

"Fibromyalgia syndrome treated with structural integration Rolfing®"[1]

Subjects: Thirty female subjects aged 28-62, diagnosed with fibromyalgia according to American College of Rheumatology criteria, who had been in conventional treatment for at least one year, were recruited from among outpatients attending the Pain Center, Neurological Clinic, Clinicas Hospital, School of Medicine, University of São Paulo.

Treatment: 10 Rolfing sessions of approximately 30 minutes each were provided by Dr. Stal. All patients continued routine outpatient pharmacological treatment as prescribed.

Data: Patient-completed questionnaires included a verbal numeric analog scale (0-10, "no pain" to "unbearable pain"), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). Data were collected at enrollment, the final treatment session, and 3 months followup.

Analysis: Non-parametric Friedman test.

Results: There were no dropouts. Statistically significant improvements were found pre versus post-treatment in pain, depression, and anxiety (each p<0.001). Between post-treatment and three months follow up, there were no significant changes in pain or depression, but significant improvements in anxiety continued between post-treatment and 3-month followup (p=0.028).

Conclusion: Rolfing® treatment was associated with statistically significant reductions in pre-treatment levels of pain intensity, anxiety, and depression both immediately post-treatment and at 3 month follow-up.

Funding: Dr. Stal's effort was supported, in part, by a grant from the Rolf Institute® of Structural Integration.

"Effects of structural integration Rolfing® method and acupuncture on fibromyalgia."[2]

Subjects: 60 outpatients (6 males, 54 female) aged 18 or above who had been diagnosed with fibromyalgia according to American College of Rheumatology criteria were recruited from among outpatients at the Multidisciplinary Pain Center, Neurological Clinic, Clinicas Hospital, School of Medicine, University of São Paulo.

Data: Patient completed questionnaires included the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), a verbal rating scale of pain (0 -10, from "no pain" to "unbearable pain"), BAI, and BDI. Data were collected at the initial interview, after last session, and at three-month followup.

Treatment: Each subject was randomly assigned to one of three groups: Group 1: 10 weekly sessions Rolfing (Rol) delivered by Dr. Stal; Group 2: 10 weekly sessions acupuncture (Acp) provided by two acupuncturists with > 10 years experience; Group 3: 10 weekly sessions of Rolfing and of Acupuncture (Acp+Rol) on the same day. In addition, all subjects continued regular outpatient medication, including pharmacological treatment.

Analysis: Generalized linear model.

Results: There were no dropouts in any treatment group. There were statistically significant (p<0.001) improvements pre to post treatment within each group in FIQ, BAI, BDI, and pain. Between post treatment and follow up there were no significant changes in FQI, BAI, or BDI, i.e. improvements relative to pre-treatment levels remained significant (p<0.001). Pain increased significantly between post treatment and follow up (p=0.002), but remained significantly lower than pre-treatment levels (p<0.001). Comparing pre to post treatment changes between the three groups, the FQI improvement was greater in Acp alone compared to Acp+Rol (p=0.025). The BAI improvement was greater in Acp alone compared to Rol (p=0.043) and also compared to Acp+Rol (p=0.012) Note that the outcomes of comparisons between groups as summarized here are corrections of comparison outcomes displayed in the published article. (Personal communication with Paula Stal, December, 2015).

Conclusion: Each of the three treatment regimens was effective with statistically significant reductions in pre treatment levels of pain intensity, anxiety, depression, and quality of life both immediately post treatment and at 3 month followup. Rolfing® and acupuncture are useful as adjunctive therapies for fibromyalgia patients.

References

1. Stal P, MJ Teixeria. (2014). Fibromyalgia syndrome treated with the structural integration Rolfingr method. Rev Dor Sao Paul0, 15(4), 248-52.

2. Stal P., Kosomi JK, Faelli CYP, Pai HJ, Teixeira MJ, Marchiori PE (2015). Effects of structural integration Rolfing method and acupuncutre on fibromyaligia. Rev Dor Sao Paul0, 16(2), 96-101.

© Copyright Eric Jacobson 2016